Top Secret Esoteric Background #1:

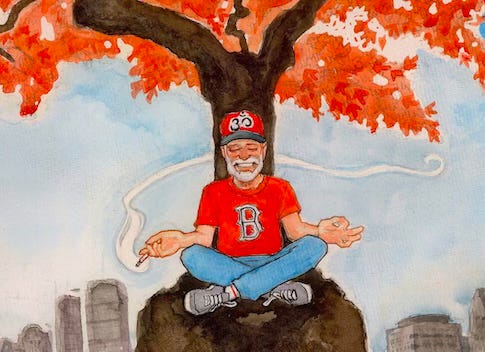

What's a Nice Guy Like the Buddha Doing in a Place Like This?

This background chapter provides (or undermines) the underlying esoteric/spiritual premise for “The Man Who Woke up the Buddha.”

Key Links:

Back to Episode #1 • Table of Contents • Family Tree

While presented as fiction, The Man Who Woke up the Buddha is basically a true story. Or at least as true as a lot of spiritual books considered gospel. Because the truth is often more amusing, irreverent, profound, and wise than you would imagine.

Take a guy like the Buddha or a woman like Mother Mary. They didn’t use up all their individual spiritual power in one lifetime. They came and went under different “guises” in multiple lifetimes.

The Tibetans keep it simple. They just put a new number at the end of each new Dalai Lama’s name. The current one is a wonderful guy named Tenzin Gyatso, who is considered the 14th Dalai Lama. So instead of calling our hero Sid, we could call him something like Siddhartha Gautama v.15.1.2. But who’s counting?

Fortunately, for Sid, his Buddha nature hadn’t crystalized1 until he was in his sixties, instead of when he was a kid. A name like that probably would have made life a little difficult on the school playground and, these days, could easily get him kicked out of the country—even if he managed to get himself born here.

Admittedly, when the Buddha first looked out from Sid’s seizure-addled eyes, he wondered if he’d made a wrong turn somewhere out there in the etheric.

The legendary “Awakened One” usually found himself working within someone of more consequence than a fun-loving, irreverent, rapidly-aging businessman with terminal cancer.

But he quickly realized that Sid’s wide-open mind, unbridled imagination, and easy-going willingness to put his subconscious at the service of any lost or found soul who needed a body, made up for his spiritual lassitude and relatively ordinary existence.

If anything, Sid’s lack of preconceptions about the historical Buddha could make things easier since, as usual, the Buddha now wasn’t the Buddha then. He’d come back to go forward. And try to take some humans with him who could then take others with them who could take others with them.

It was a great plan in theory. In fact, it was the original idea of the Bodhisattva thing—which seemed like an evolutionary slam dunk when he and some of his cohorts on, what I’d guess you’d call, the Cosmic Creation Team dreamt it up. Unfortunately, they underestimated the human obsession with taking everything personally—to celebrate their suffering instead of getting free of it; to live only in the present when there was so much fun going on in the past and future. (Sure, the now had its moments, but it had proven to be kind of addictive. People kept on wanting to experience more and more of it.)

And, if that weren’t bizarre enough, these humans had managed to use their high-powered, albeit twisted circular logic to get attached to the experience they called enlightenment.

The people who went this route also found to their dismay that there was nothing they could do about the pain and suffering their fellow humans continued to inflict on each other—a phase of human evolution that was supposed to have ended centuries ago. The best tactics they could come up with were variations on praying for peace or meditating on it, practices which, while they at least temporarily cleared the etheric air around the conflicts, practically speaking didn’t do a whole lot to end them.

For centuries, the Buddha had just kept shrugging his shoulders and throwing himself back into the fray to see if he could get even maybe a few of these humans to, as he put it, lighten the f— up.

This time, however, he was ready to try something different. Clearly shocking people, teaching them new lessons, showing them new practices, flooding their beings with compassion or changing their everyday behavior or experiences, just weren’t doing the trick.

The revolutionary, or rather evolutionary, insights that he would use this Sid guy to scatter to the winds, would have to be revealed in glimpses so fleeting that people would barely realize they’d heard or seen them. And, if nothing else, at least people wouldn’t be left with a thousand more pages of holier-than-though gobble-di-gook to use as justification for killing each other.

However you looked at it, there was a lot of work to do and not a whole lot of human time left in Sid’s life to do it.

Well, the Buddha thought, with a suspiciously Sid-like grin. What’s the point of getting free of suffering if you don’t know how to have fun? So let the games begin.

Thanks for listening. I hope you enjoyed this other perspective on spirituality which Sid and the Buddha will continue to put light on and make light of as our series continues.

Return to Table of Contents to pick up where you left off!

Naturally, I’d really enjoy hearing what you think of this perspective.

Can’t think of a better word at the moment. The Buddha doesn’t usually take on a lifetime start to finish. He gets in while the getting’s good and leaves when he’s completed whatever he came here to do. It’s complicated.