The Bugs Bunny Sutra (Redux)

This is the last summer re-run before we return to The Man Who Woke up the Buddha—the ongoing (mis)adventures of an ordinary businessman named Sid, who has realized that he is the Buddha, and the Buddha, who has realized he has to find a way to manifest his evolving truth in this, his latest and strangest incarnation.

With all due respect to Sid and the Buddha, the following post is easily the most spiritual, esoteric, wise, profound, and irreverent as anything I’ve had the honor of writing.

I owe much of my early education in the questionable arts of double entendre, timing, alliteration,1 dramatic tension, bad puns, and instant karma to a man named Chuck Jones and his collaborators.

Did I say timing?

Chuck (I don’t think he’d mind if I call him “Chuck”) is best known for channeling Bugs Bunny and many of his Loony Tunes cohorts. Bugs is a “bodhisattva”—a perfectly evolved being who has returned in earthly form to help guide others to completion.

He shares his wisdom freely: “Don’t take life too seriously. You’ll never get out alive!” and has nothing but a mildly bemused love for the creatures he encounters. Even when the infamous Elmer Fudd trains a shotgun on Bug’s face, our hero responds with calm aplomb. And when the other shoe drops—typically in the form of something like a ten-pound anvil on Elmer’s head—Bugs uses it as a teaching moment to illustrate the eternal, and yet unnecessary, suffering of humans who live from anger and fear.

Despite this sage instruction, Mr. Fudd seems incapable of being free of judgment, frequently accusing his adversary of being just a “silly wabbit.” Whereas Bugs, even in the face of overwhelming firepower, maintains his cool detachment and says, with as much compassion as flippancy, “Remember Doc! Keep smiling!”

While you could argue that Bugs strays from at least one of the eightfold paths when he gloats, “Of course, I talk to myself. Because sometimes I need expert advice,” to him it’s just a statement of fact that proceeds, albeit counter-intuitively, from his other seminal insight: “Y’know, maybe there is no intelligent life out there in the universe after all.”

Chuck Jones once said: “Bugs is who we want to be. Daffy is who we are.” Personally, I’d rather be Road Runner: that inscrutable master of the Tao, perfectly enlightened Zen Master, and animated incarnation of the Dalai Lama. RR (I don't think they'd mind me calling them "RR") finds a myriad of ways to instruct Wile E. Coyote in the laws of instant karma, without saying a word (beep beep) or lifting a finger (they don't have fingers).2

Road Runner also gives the classic Greek philosophers a monosyllabic run for their money. In one version of a recurring shtick, Wile E. Coyote paints a tunnel opening on a huge boulder, figuring that Road Runner will go splat!!! Instead, the galloping guru of the desert runs right through it. Baffled, Wile E. tries it himself, and, sure enough, he too can walk right into the tunnel. But when he turns around he finds he can’t get out. Top that, Plato.

It was somehow reassuring when I brought up the name Chuck Jones to my autodidact illustrator Echo, as we talked about the art for this essay. Since Echo is a disturbing number of decades younger than me—and Chuck Jones died around the time they were born—I assumed Echo would never have heard of him. Instead, their face immediately lit up: “Chuck Jones was a genius,” Echo said, before elaborating on Chuck's influence on the art of illustration.

But what about voice? Would my voice be all that different if I was growing up today?

The other evening I was assaulted by ads for Thor: Love & Thunder during halftime of a basketball game. On the surface, its characters seem a world—or a universe—apart from Bugs et. al. When I was a kid, the goal was to anthropomorphize animated characters. Now, it seems, the goal is to animate human characters. But both rely on the same combination of gratuitous violence and irreverent humor. And Bugs could break the fourth wall with the best of them.

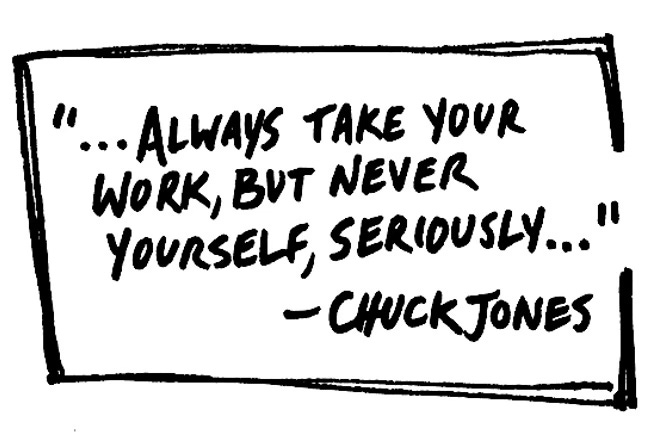

Well, only a fool and/or epistemologist would try to determine which aspects of a writer’s voice come from nurture and which come from nature. Ars may be longa, but the life of a writing style can be pretty brevis. Fortunately, Chuck Jones dissolved the distinction:

"The rules are simple. Take your work, but never yourself, seriously. Pour in the love and whatever skill you have, and it will come out." — Chuck Jones

E.g., “Watch me paste that pathetic palooka with a powerful, pachydermous, percussion pitch.”

RR is also presumably gender-fluid but that’s a whole other topic. (Yes, Tweetie Bird, I’m talking about you.)