Originally Published in the Lock Raven Review - January 9, 2023

Maslow assumes it’s a book of crossword puzzles. Or one of those Sudoku things. The girl never looks up when he puts his key in the door but slides over instinctively to make sure she’s not blocking his way.

Maslow works in a building full of artists and musicians half his age; his office is a throwback to the ’40s. Raymond Chandler could put his name on the etched frosted glass, keep a bottle of whiskey in the bottom drawer, put his feet up on the desk, light a cigarette, and wait for a blonde with well-turned ankles to walk in. The girl on the stoop isn’t blonde. And he doesn’t think Chandler’s femmes fatales had bracelets tattooed on their ankles. Or bright-green streaks in their hair. He never knew what a well-turned ankle was anyway.

Most afternoons she and her friends loosely gather and re-gather like waves far out to sea. Drinking coffee from the café two doors down and smoking cigarettes. Usually hand-rolled. When Maslow sees one with a branded pack, American Spirit of course, he figures they just came into an inheritance. Most of them start working about the same time he’s done for the day. The next morning there’s always a pervasive aroma of paint thinner with a top note of tobacco and reefer. Occasionally a beer bottle is outside a door. But never more than two.

Maslow has seen her in animated discussions with the others. But usually, they talk around her, gathered on the sidewalk in a particular configuration that, whether intentionally or not, creates a kind of protective force field.

He figures she’s a late-twenty-something writer in the midst of a crushing Saturn return and major depressive episode. Keeping her head down and doing crosswords until it passes. During his breakdown, he’d read mysteries. By the time he came up for air two years later, he’d gone through the complete works of Sherlock Holmes, Dashiell Hammett, Agatha Christie, and, of course, Raymond Chandler.

One morning Maslow throws caution to the wind. “Sixteen down,” he says, “‘compulsive fragrance,’ nine letters, obsession.” Like she’s doing the Times puzzle for the day and he already finished it.

Her head only lifts a few degrees but she kinda smiles. They both know that he’s off by several decades and even more cultural divides. But she’s doing her best to be gracious about it.

Maslow spends an inordinate amount of time preparing for their next encounter. “Thirty-four across… ‘false instrument,’ four letters, is lyre,” he says with a cheerful, self-effacing lilt in his voice.

She barely acknowledges that one. The same afternoon she’s still there when he goes out for coffee. Fortunately, he has another one ready: “Twelve across, ten letters, ‘mental way,’ is psychology.”

This time she pauses and taps the pencil thoughtfully on her cheek, lead side in. “Psychopath,” she mutters to herself.

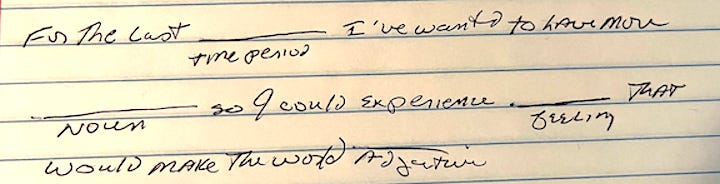

He doesn’t see her for a week. Then she’s back like she never left. “Give me a time period,” she says. He already has the door open and one foot inside.

“Like a day or a week?”

“Which one?” she says impatiently.

“Okay, a week.”

“A noun,” she demands.

The word sounds vaguely old-fashioned coming from her lips—the top one pierced…a tiny, silver ring. He puts his laptop bag down but stays standing: “I don’t know. Money?” He catches himself. “Flowers? Trees? Sunshine?”

“Stop asking me. Tell me. Fast. You’re not supposed to think.”

“Fine. Pencils.” That’s a good one he thinks.

She sighs. He’s not taking her seriously. But writes it down. “A feeling,” she snaps like a drill sergeant. “Quickly!”

“Ecstasy!” he says back like he’s obeying an order.

She sighs again. She expected something more counter-intuitive. “Okay, an adjective.”

“Blissful.”

She writes it down, nods, and mumbles to herself.

He breathes a sigh of relief. “Okay,” he says, finally accepting he can’t finesse her attitude. “What are you working on?”

She looks up, surprised to find him still there. He holds her gaze until she half-heartedly holds up her notebook.

“Like Mad Libs?” Maslow asks, trying to decipher the scrawls with underlined words.

“Kind of.”

“Making up your own?” he asks, hearing crackles of thin ice.

“Making up everyone’s.”

“Interesting,” he says like this is an everyday pleasant conversation with an everyday pleasant person. “Borges said there are only four stories to tell,” he adds, silently thanking the gods of memory for finding this one in his.

She jabs her pencil into the notebook. “Well, Borges was wrong.”

“Yeah?”

“There are twelve.”

“Really? What are they?”

“That’s what I’m working on.”

“Your Holy Grail, huh?” Maslow grimaces at how patronizing he sounds.

She ignores him. Starts writing again.

“So what’s your story?” he asks, sitting down next to her on the stoop. Neither can believe he finally did that.

She puts the book down, reaches into a floppy patchwork sequined bag, pulls out a cigarette butt, and lights it. Blows the first lungful of smoke toward, but not right at, his face. Enough to level the playing field.

He doesn’t react.

Her eyes slide off to her left, down at her pad, then back to him. “Just fill in the blanks, man.”1

A version of this story was first published in Loch Raven Review.

Good one.