Self Portrait Part 1: Coffee. Black.

This is the first of a four-part short story about life in downtown Brattleboro, Vermont, based on experiences described in my “Street Cred” series. The town is pretty much as described, and one of the two main characters (Virgil) is inspired by my friend Melvin. The story itself, including the other characters, is fiction. Any resemblance to real characters and events is inadvertent.

This is, in part, an experiment to determine the best lengths and timing for individual chapters in serial fiction. The first one here is about the length of my usual essays. The rest are some somewhat longer. I’m publishing Part 2 tomorrow and Parts 3 & 4 next Wednesday/Thursday.

Virgil wouldn’t let just anyone give him money.

Bridget first noticed him one morning in late September—a skinny guy with a wispy goatee who looked like a 1950s beat poet dressed in small-town scavenger chic. He was hanging out with Richie and some of the other regulars in front of the coffee shop she passed every day on the way to her studio. They were all on a spectrum from homelessness to sleeping at the shelter to couch surfing to barely paying the rent. And even if they had a little Social Security or SSI or a SNAP card, by the end of the month they seemed to always need a little money for junk food, cigarettes, coffee, or beer; gas money for a ride; maybe some pot...or heroin, likely cut with fentanyl.

Many were probably pushing seven or eight on the “Adverse Childhood Experiences” scale.

Virgil was blowing on his hands like it was 30 degrees out, even though it was already in the ’60s. She figured he’d spent the night outside.

As Bridget got closer, he turned his head slowly and slid a few steps away from the group to face her. She got ready for the ask, instinctively reaching in her coat pocket, but all he did was raise his head and squint his eyes like he was evaluating her in a way that felt suspiciously seductive. That made her smile—as much to herself as to him. He had to be thirty years younger. But when she reached for the door handle at the cafe, she asked, a little flirtatiously, “Can I get you a cup of coffee?”

“Well, you could, but I probably wouldn’t drink it.”

“Don’t like coffee?”

“Oh, I like coffee just fine. Black,” he said. “Like myself. Maybe a little sugar. Like myself. Not the artificial kind.”

“So?” she was confused.

“Well, I can’t say I know you well enough.”

For a long time, Bridget was a little intimidated by people on the street. Walked past them or looked down when she handed them a few bucks. But, once in a while, she saw a street person hanging out with one of the "starving artists" around town—the "kids" who shared studio/living space and worked as baristas and bartenders and servers. She knew most of them and their art—some of which was barely worth the title and others good enough to get them shows at big galleries in tiny cities or tiny galleries in big cities. She'd check in once in a while to see what they were working on…maybe offer extra materials. Some had even taken art classes with her when they were teenagers.

Increasingly, when she stopped to talk with one of them, they were trading street gossip and more with the folks who regularly asked her for money. Hanging out with them gave her a certain amount of street cred. She began to be referred to as that "good-looking older lady—the artist one—who wears the strange blue shirt and the rock-and-roll t-’s." It made her feel safer when she heard that she was known for being straight with them.

"She's OK. Don't f---with her." Richie always said when anyone bad-talked her or suggested she'd be easy to con out of some money. "And don't lie to her." (Of course, truth wasn't Richie's strong suit either.)

The “strange blue shirt” was a French workman’s jacket her brother had picked up for her in Paris in the ‘70s. The t-shirts were all vintage—the Jim Morrison one with his hair made up of song titles; the signature Woodstock T with the peace dove on the neck of the guitar; and, the street favorite…just the word "Cash,” from a Johnny Cash tour in the ‘70s or ‘80s. She also had a 1972 George McGovern “Come Home America.” They probably wondered which band George had been in.

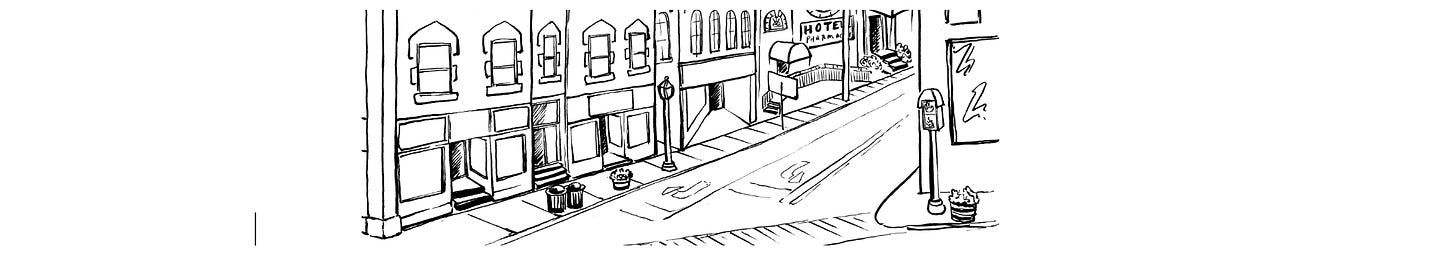

Bridget’s studio was in downtown Esteyville, a place that had never been able to decide whether it was a city or town. Everything she needed was in walking distance: a bookshop, art supply store, library, museum, Co-op, and an assortment of independent retail stores and restaurants. The two-block-long line of century-old red- and yellow-brick buildings on Main Street had turned their backs on the river that brought the earliest settlers, which gave her studio an unobstructed view of the mountains to the east.

There were also two coffee shops. She usually stopped at the one next to her entrance, unless she had an overwhelming desire for a maple walnut scone which they only baked at the one across the street.

Bridget was a portrait painter. A good one. The kind whose paintings say more about the person than the artist. Something that is surprisingly rare. Especially in watercolors, which can be terribly unforgiving. Her technique was solid, but her real strength was finding some holographic trait that revealed the whole person. Often an eye—what it showed and hid; or the mouth, where something as simple as a single tooth or a particularly low smile line could tell her more about her models than they knew about themselves.

Virgil was still there when she walked out. “Hey,” she said, feeling oddly on guard. He nodded back and said, “You have a nice day.” Long and drawn out. Southern accent.

She wanted to paint him. Badly.